Old books? Oh, dear!

We have abandoned Tradition (note the capital T) generally, but more specifically we have turned our backs on our artistic and literary culture, a culture which has at least a 3000-year-old heritage (taking us back to Homer) and possibly 4000+ years if we consider the Bible or even epics such as the Babylonian Gilgamesh. And just as society fragments when we forget traditions, especially those of a moral and social nature, so literature fragments, and we end up not with literature but with non-literature masquerading as literature. This has very serious consequences because literature is the prime repository of who we see ourselves as being, and once it becomes a contaminated source, so then – as with Pandora’s Box – other evils are unleashed into society. As Tim Stanley writes (Whatever Happened to Tradition? 2021): ‘Across the West there is a dearth of purpose and spirit: we can’t agree on who we are or what we’re about, or even if these big existential questions matter.’ The Cornell Professor, Allan Bloom, in his seminal book, The Closing of the American Mind (1987), puts his finger on one particular issue when he says: ‘The cause of this decay of the family’s traditional role as the transmitter of tradition is the same as that of the decay of the humanities: nobody believes that the old books do, or even could, contain truth.’

Old books? Oh, dear! No truth (‘What is truth?’ as Pontius Pilate queried) and no relevance; for the scrap heap then? Let’s look at this issue, then, in a little more detail. And first, consider what literature – and poetry particularly – should be. To understand that, we need to use traditional writings naturally! To keep it simple, I would say that poetry has to represent the good, the true and most importantly of all, the beautiful. Philosophical and religious texts can be good and true, but it is the especial quality of literature – of poetry – to be beautiful.

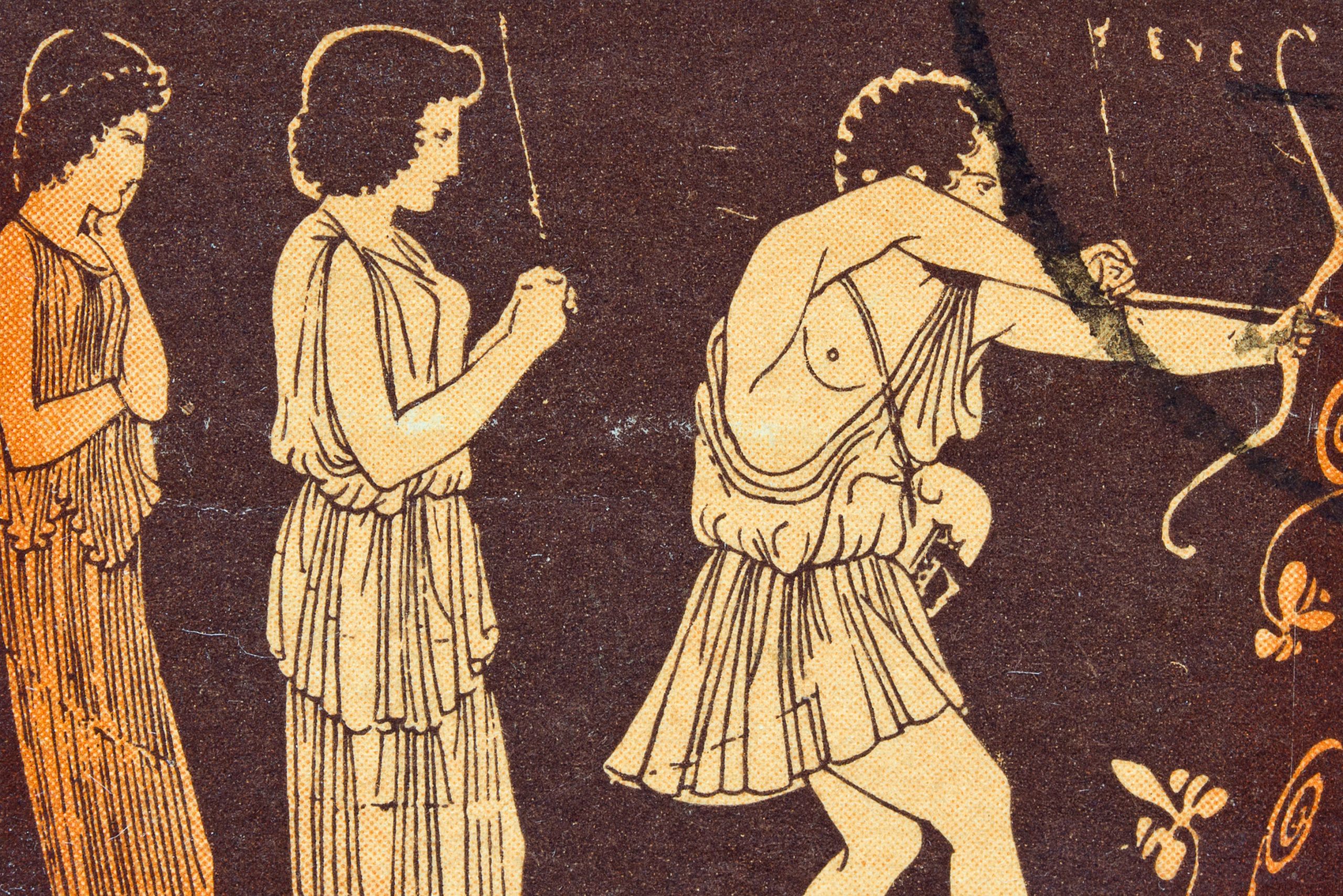

Now before going any further, it is important to debunk one implication of this which the modern mind just loves to deduce and mock: namely, that we want saccharine, bland and cutesy writings; a sort of literature like an old-fashioned Disney film – no sex, no ‘real’ violence, and no ‘issues’ that might tax us; in other words, sugary versions of pure nostalgia and escapism. But any consideration of, say, the great traditional and even sacred (for example, The Psalms) texts such as Homer or Dante or Shakespeare would utterly refute this. But unlike modern and post-modern texts, which simply revel in sex, violence, horror, perversion and revulsion for their own sakes – and for the sake of being ‘real’ and ‘realistic’ – the ‘classics’ frame these things so that they are – despite the horrors of life, especially modern life – still ‘good, true, and beautiful.’

Homer is full of violence, but it is profound and true to human nature; and alongside it go other qualities, such as when at last the anger of Achilles is satisfied, and with his enemy, king Priam, both men mourn together and suffer their respective losses. Through this their common and shared humanity is established. Dante explores sex, violence and revulsion and more besides, but always in the context of the first line of the poem: Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita – ‘in the middle of OUR life,’ not just his. We are journeying to heaven with him, and this provides an overarching meaning to all the troubles we experience on Earth. And as for Shakespeare, where to begin? So many works – but who matches Macbeth in ambition, treachery and violence? How deep, though, the depiction of all this; and how inevitable its outcome, demonstrating – though with some degree of ambiguity which, for example, Polanski’s film version evinces – goodness in its triumph over evil. One genius aspect of this triumph is of course the fact of how evil defeats itself, although seemingly invincible.

Continue reading the next discourse in the series: Why the classics?